Cutaneous metastasis as an initial presentation of lung adenocarcinoma with KRAS mutation: a case report and literature review

Introduction

The skin is an uncommon metastatic site of internal malignancies. Generally, cutaneous metastasis develops after initial diagnosis of the primary internal malignancy and late in the course of the disease. In very rare cases, cutaneous metastasis may occur at the same time or before the primary cancer has been detected (1). In a large review by Lookingbill et al. (2) including 7,316 cancer patients, skin involvement as a presenting sign was seen in only 0.8%. Being the first sign of presentation, cutaneous metastasis can often be biopsied to help find the primary cancer. Among the cutaneous metastatic cancers, lung is the most common primary site (24%) of underlying malignancy in men, and the fourth most common primary site (4%) in women (1). The presentation of cutaneous metastasis in lung cancer portends a poor prognosis with an average survival ranging between three and five months in the majority of studies (3-5). In this report, we describe an unusual case of KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma metastasizing to skin followed by multiple internal lymphadenopathies and profuse pericardial and pleural effusions that clinically mimicked a lymphoma at the time of initial diagnosis.

Case presentation

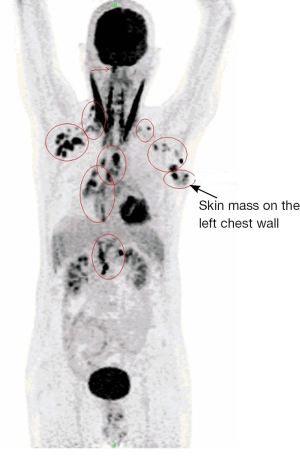

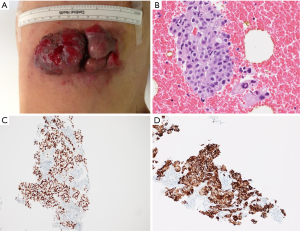

A 61-year-old male, non-smoker, who had worked as a coal-fired industrial boiler operator, was transferred to our hospital for dyspnea and pericardial effusion. Three months before admission, the patient had noticed a firm, painless, reddish skin lesion that was growing rapidly from a tiny papule to a bean-sized nodule on the left side chest wall, and had shown no improvement after treatment with antibiotics and topical steroids at a private dermatology clinic. The skin nodule continued to grow to a mass over one month period. Later the patient started to suffer from shortness of breath, and found to have significant pericardial effusion and 1.5 L of pericardial fluid was drained at a local hospital. Subsequent whole body PET/CT revealed moderate left pleural effusion and multiple foci of lymphadenopathy in bilateral deep cervical, axillary, supraclavicular, occipital, hilar, paraaortic lymph nodes. The intense uptake of the radiotracer fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose was present within the enlarged lymph nodes and in the left chest wall skin mass (Figure 1). The patient was given a suspected diagnosis as lymphoma and was transferred to our tertiary care center. On admission, his condition deteriorated with worsening dyspnea at rest, which was not associated with fever, chills, cough, chest pain, orthopnea, or edema on lower extremities. The patient reported 20 pounds unintentional weight loss over two months with poor appetite. Cutaneous examination showed sharply demarcated, dark red, cauliflower-like mass measuring 11 cm × 4.5 cm in diameter and protruding 3 cm above the left side anterior chest wall, accompanied by sanguineous exudation. The adjacent skin contained signs of inflammation with erythema (Figure 2A). A biopsy of the skin mass was performed and revealed metastatic adenocarcinoma of lung origin (Figure 2B) with diffuse strong nuclear staining for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) (Figure 2C) and membranous staining for cytokeratin 7 (CK7) (Figure 2D) as well as the negative staining to cytokeratin 20 (CK20), CDX2 and p63 which are the markers for colon cancer and for squamous carcinoma. KRAS mutation was detected in codon 12, which also points towards a metastatic adenocarcinoma of lung origin. EGFR and ALK mutation testing were negative. The patient underwent an echocardiogram which showed a large posterior pericardial effusion with echocardiographic evidence of right ventricular collapse. Pericardial window was made emergently through a left video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) for drainage of his pericardial effusion. Pleural and pericardial effusions were evacuated and sent for cytology. Malignant cells with positive immunostain of TTF-1 were found in both pleural fluid and pericardial fluid, which further confirmed metastatic adenocarcinoma from lung origin. Given the diagnosis of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma with multiple distant metastases, the patient received palliative chemotherapy (carboplatin + paclitaxel) for two cycles. Unfortunately, there were no improvements on either the cutaneous metastatic mass or his general condition.

Discussion

Generally, cutaneous metastases are encountered in 0.7-9% of all patients with cancer and as such the skin is an uncommon site of metastatic disease when compared to other organs (6). Dissemination of visceral malignancies to the skin is rather rare and usually occurs in a later stage of the disease. However, cutaneous metastases may be the first indication of the clinically silent visceral malignancies. In case of lung cancer, metastasis to the skin is much less frequent than that to other organs (brain, bone, liver and adrenal glands). The currently two largest reported studies of cutaneous metastases secondary to lung cancer: A meta-analysis in 2003 showed the incidence of cutaneous metastases in lung cancer was 3.4% in 89 patients among 2,597 subjects (7). A retrospective study in 2012 indicated that 2.8% of 2,130 patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) showed cutaneous metastases as an initial presentation (3). Clinically, lung cancer may be initially detected by cutaneous metastasis, since the primary lung lesion often remains quiescent, such as in our case.

Cutaneous metastasis can manifest as a nodule, ulceration, cellulitis-like lesion, bullae or fibrotic process. Generally, the nodular type is the result of hematogenous metastasis, and is likely to be the most common. Nodules are painless, mobile or fixed, firm or rubbery, discrete or multiple. They vary in color from flesh tones to red-purple, or blue-black and vary in diameter from 5 mm to 6 cm (8). Multiple lesions are usually grouped. They initially grow rapidly, and then more slowly, and may necrotize or ulcerate (9). The regional distribution of the cutaneous metastasis, although not always predictable, is related to the location of the primary malignancy and the mechanism of metastatic spread. The relative frequency of cutaneous metastasis correlates with the type of primary cancer, which occurs in each sex. For instance, lung and breast carcinomas are the most common primaries that send cutaneous metastasis in men and women, respectively. The head and neck region and the anterior chest are the areas of greatest predilection in men. The anterior chest wall and the abdomen are the most commonly involved sites in women (6). While certain cancer types are characterized by random distribution for cutaneous metastasis (liver cancer), a number of cancers demonstrate a colonization preference to the region of origin: lung cancer to the supradiaphragmatic (mostly chest) and colorectal cancers to the infradiaphragmatic (abdominal) skin regions. In certain cases, however, cutaneous metastasis develops more frequently at specific distant locations, as evidenced by the dissemination of renal cancer to the head and neck region (10). These findings are clinically relevant and useful especially in patients where cutaneous metastasis is the first indication of a malignancy. The cutaneous metastasis observed in our case located on the chest wall. It was a solitary nodular type and grew rapidly to an unusual big size associated with necrotizing and ulceration.

Physically, cutaneous metastatic lesions due to lung cancer are indistinguishable from those due to carcinoma originating elsewhere in the body. A strong and diffuse nuclear expression of TTF-1 immunostain is characteristic of primary lung cancer and thyroid carcinoma, which is helpful for identifying the histological origin of primary cancer. Mutually exclusive to EGFR and ALK mutations, KRAS mutants are detected mainly in adenocarcinomas, and show association with progressive disease status. Given the positive expression of TTF-1 and KRAS mutation detected in our patient’s cutaneous metastasis, we further confirmed the primary malignancy as lung adenocarcinoma. However, thus far the relationship between the histological type of lung cancer and the occurrence of cutaneous metastasis has not been well-defined. Schoenlaub et al. (11) demonstrated that lung large cell carcinoma had the greatest tendency to metastasize to the skin and lung squamous cell carcinoma the least. On the contrary, lung adenocarcinoma had the greatest tendency and lung large cell carcinoma the least in Hidaka’s report (12). So far, we have not found any reports regarding gene mutation analysis in lung cancer patients with cutaneous metastatic lesions. Therefore, this is the first case report to show that KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma can be associated with cutaneous metastasis.

Lung cancer patients with cutaneous metastasis are not likely to be cured. Such metastasis signifies a fast-growing aggressive primary lung carcinoma. These patients have an extremely poor prognosis with an average survival ranging between three and five months in the majority of studies (3-5). Generally, therefore, only palliative chemotherapy is offered. Radiation therapy to the cutaneous metastasis is indicated if associated with severe pain or bleeding. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been in use as cancer therapeutics for nearly a decade, and their utility in targeting specific malignancies with defined genetic lesions has proven to be remarkably effective. Recent efforts to characterize the spectrum of genetic lesions found in NSCLC have provided important insights into the molecular basis of this disease and have also revealed a wide array of tyrosine kinases that might be effectively targeted for rationally designed therapies. Even though KRAS mutations were identified in NSCLC tumors more than 20 years ago, we have only just begun to appreciate the clinical value of determining KRAS tumor status. KRAS mutations occur more frequently in lung adenocarcinomas (approximately 30%) and less frequently in the squamous cell carcinomas (approximately 5%) (13). KRAS mutation is a poor prognostic factor. Recent studies indicate that patients with mutant KRAS tumors fail to benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy and do not respond to EGFR inhibitors. Activating mutations in EGFR gene are both prognostic and predictive in that they are associated with improved survival, irrespective of therapy, and are associated with a significant response to EGFR TKI such as gefitinib or erlotinib (14,15). Patients with EGFR mutations also show a significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) compared to standard chemotherapy (16). This discovery has dramatically changed the clinical treatment of lung cancer in that it almost doubled the duration of survival for lung cancer patients with an EGFR mutation. More recently, fusions involving ALK gene were discovered in NSCLC (17). Patients with ALK gene rearrangements demonstrate significant objective response rates and PFS times to the oral ALK inhibitor crizotinib (18). The prognostic significance of ALK is somewhat unclear. Our patient did not receive these targeted therapies due to a lack of mutations in EGFR and ALK. He also did not respond to the chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel.

Conclusions

We have reported the first case of KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma with remarkable cutaneous metastasis and rapid progression who did not respond to chemotherapy. Since KRAS mutations do not currently predict for benefit from targeted drugs and are associated with a worse survival, there is a clear need for therapies specifically developed for patients with KRAS-mutant NSCLC.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

References

- Mollet TW, Garcia CA, Koester G. Skin metastases from lung cancer. Dermatol Online J 2009;15:1. [PubMed]

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. A retrospective study of 7316 cancer patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;22:19-26. [PubMed]

- Song Z, Lin B, Shao L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis as a initial presentation in advanced non-small cell lung cancer and its poor survival prognosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2012;138:1613-7. [PubMed]

- Giroux Leprieur E, Lavole A, Ruppert AM, et al. Factors associated with long-term survival of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Respirology 2012;17:134-42. [PubMed]

- Sörenson S, Glimelius B, Nygren P, et al. A systematic overview of chemotherapy effects in non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Oncol 2001;40:327-39. [PubMed]

- Hussein MR. Skin metastasis: a pathologist’s perspective. J Cutan Pathol 2010;37:e1-20. [PubMed]

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J 2003;96:164-7. [PubMed]

- Dreizen S, Dhingra HM, Chiuten DF, et al. Cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases of lung cancer. Clinical characteristics. Postgrad Med 1986;80:111-6. [PubMed]

- Vila Justribó M, Casanova Seuma JM, Portero L, et al. Skin metastasis as the lst manifestation of bronchogenic carcinoma. Arch Bronconeumol 1994;30:314-6. [PubMed]

- Kovács KA, Hegedus B, Kenessey I, et al. Tumor type-specific and skin region-selective metastasis of human cancers: another example of the “seed and soil” hypothesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2013;32:493-9. [PubMed]

- Schoenlaub P, Sarraux A, Grosshans E, et al. Survival after cutaneous metastasis: a study of 200 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2001;128:1310-5. [PubMed]

- Hidaka T, Ishii Y, Kitamura S. Clinical features of skin metastasis from lung cancer. Intern Med 1996;35:459-62. [PubMed]

- Roberts PJ, Stinchcombe TE, Der CJ, et al. Personalized medicine in non-small-cell lung cancer: is KRAS a useful marker in selecting patients for epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapy? J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4769-77. [PubMed]

- Douillard JY, Shepherd FA, Hirsh V, et al. Molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib and docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer: data from the randomized phase III INTEREST trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:744-52. [PubMed]

- Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2129-39. [PubMed]

- Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 2009;361:947-57. [PubMed]

- Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature 2007;448:561-6. [PubMed]

- Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1693-703. [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Liao H, Wu S, Karbowitz SR, Morgenstern N, Rose DR. Cutaneous metastasis as an initial presentation of lung adenocarcinoma with KRAS mutation: a case report and literature review. Stem Cell Investig 2014;1:6.